This article originally appeared on Medium.

In this article:

- Why state management is a better solution to prop drilling in large apps

- State management allows you to update pages without a refresh.

- Redux and MobX are fine libraries, but not for everyone.

- What are the different kinds of state and where to store them.

- React apps have two layers.

- The importance of understanding shared v non-shared components.

One thing I love about working at OpsRamp is how we always come together to figure out new ways to manage complexity or achieve difficult development goals. Take, for example, managing application states. It’s historically one of the biggest challenges in front-end development. We’re a lean team, so we needed to figure out a better way. In this article, I’ll address how we accomplish this with React at OpsRamp, and how you can apply some of these practices in your own workday.

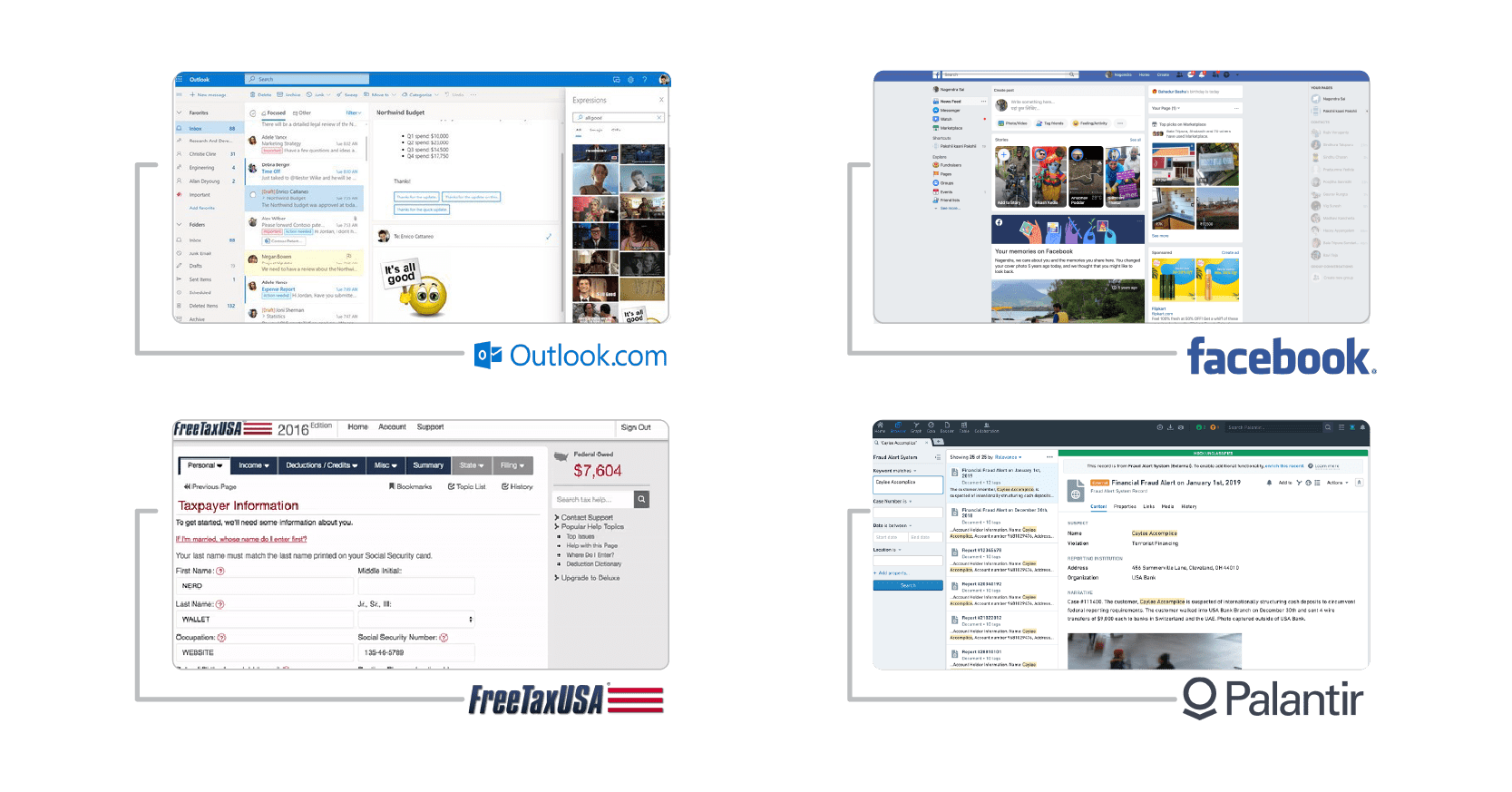

Think about the most complex frontends you’ve used, sites that made you wonder: “How did they create this”? Here are some of mine: What makes these frontends complex?

What makes these frontends complex?

State management. The frontend “knows” a lot of things, and these things interact with each other in non-trivial ways. So in my view, state management is the core problem when developing a UI. Here are some things I wish I knew about state management earlier.

#1 - State management is how you mitigate prop drilling.

To build a non-trivial React application, you need to consider state management. You don’t need to use a third party library: you can use Context. But you do need to figure out how to store global state that can be accessed anywhere in your application.

Example: dark mode support

Say your app has a dark mode. All your rendered components must know what theme is on, so they can render the UI in the right color. Other examples of global UI state include whether the user is logged in, the logged in individual’s username, and the value of the global search box.

Prop drilling isn’t the answer

Context didn’t exist when I started learning React, so to solve this problem, I prop drilled. As your app gets larger, prop drilling becomes impractical.

State management is the answer

What you need to do is store your theme setting in a Redux or MobX store, or in a plain JavaScript object, and pass it to all your components using Context. I had no idea state management was the solution to the prop drilling problem until I learned about Redux, out of curiosity. To make things worse, many articles say you can build non-trivial web apps without state management, which initially deterred me from even learning about it.

#2 - State management is how you update your page after creating/updating data, without a refresh.

The problem

Say you’re writing a to-do app. After the user creates or renames a to-do item, you’d like to update only the to-do list component — but not refresh the page. How do you do this?

The solution

The solution is to store the list of to-do items in a global store in the client, along with a method for re-fetching the list of to-do items from the server and updating our store. Then, your to-do list component reads the list of to-do items from your global store. After the user creates or updates a to-do item, call the method for re-fetching the list of to-dos, which updates your global store and updates your component. I think of the list of to-do items on the client as a client-side cache: a subset of the data on the server.

#3 - Manage your state by storing it in the right places

Don’t just put all your application state into whatever state management library you choose. Instead, recognize that your application has several different kinds of state. I’m inspired by James Nelson’s post on this topic.

- Data + loading state is the list of to-do items your frontend renders and shows whether the list is loading. Put this into Redux/MobX/etc.

- Global UI state refers to whether the user is logged in, value of a global search bar. The server doesn’t store this data at all. Use Redux/MobX/etc.

- Local UI state is a dropdown which has expanded, for example. The rest of your frontend doesn’t care about this. Use component state.

- Form state is the values of fields in a form and is a subset of the local UI state. Use a library like Formik to treat the form as a controlled component.

- URL state is the route the user is on at the moment. Read and update window.location; don’t create a second source of truth.

- Page state is where you have a page in which components interact with each other in a complex way, but not with components on other pages. Create a Redux/MobX store just for the page (or pass down a plain JS object with Context)

#4 - Learn other state management libraries in addition to just Redux

Redux is probably good enough for your application, but I didn’t like using it. Why do I need to worry about normalizing the data from my server on my client? Why do libraries like Redux ORM need to exist? I don’t want to re-implement a bunch of my server-side code on the client. Why do I need to touch multiple files and write a lot of boilerplate code in order to add a simple feature? What is an action/action type/action creator/reducer/store again?

I understand the benefits of writing immutable, functional code, but writing Redux reducers feels needlessly unintuitive. I’d like to simply make an API call in an action and update my Redux store without learning and using Thunk or Saga.

Switching to MobX

Then I learned MobX. Each store is just a plain JavaScript class. There’s no boilerplate. Each piece of state in a store is just a class variable. Actions are just methods in the class with an @action decorator. You can make API calls in your actions just like you normally would; wrap the code that updates your state after the call with runInAction. It supports observability, which I don’t use much myself, but is a useful tool.

Find the right library for you

MobX may not be the solution for you. It may be apollo-link-state, unstated, xstate, or a home-brewn solution using Context. Keep learning different libraries until you find one that fits your requirements.

#5 - Your React app has two layers

State and view layer. I think of a React app as having two layers:

-

A JavaScript object, also known as your state, and methods that update it.

-

React code, the view layer, which turns that JavaScript object into Document Object Model (DOM) elements.

This is what people mean when they say “UI is a function of state” and “React is just a view layer.” By embracing this paradigm, you can write testable, functional code, decoupled from your UI, for managing your state. And your UI becomes easy to write. You have a JavaScript object with all the data your UI needs, structured in the way your UI wants it, with methods for updating this JSON object. Write your components easily with this “API”.

Keep in mind that not all state management libraries store state internally as a JavaScript object, but this is the way I like to think about it. Of course, in practice, not all your state should be in your global state, as I write above.

#6 - Shared vs non-shared components

When I first started writing with React, I put my data fetching code in my components. But this meant I couldn’t use a component in another place for its UI only.

-

Fetching data in my container components. Then, I read Dan Abramov’s article on presentational vs container components. At first, I put my data fetching code in my container components, each of which rendered a presentational component. But I realized I needed to put my data fetching code in MobX in order to update the UI after creates and updates (see #2).

-

Fetching data in MobX actions. Next, I put my data fetching code into MobX actions. Each container component connected to my MobX store and rendered a presentational component, passing data and methods from my MobX store as props as needed. Unfortunately, this forced me to write a lot of boilerplate container components that effectively did nothing.

I concluded that the right distinction is shared vs non-shared components.

- Shared: Components you’ll need to render in more in than one place in your app and which can be either presentational or container. Examples: UserSelect, Button

- Non-shared: Components you’ll only render in one place. Examples: UserTable, GlobalSearchInput

The presentational vs container component distinction assumes that you want to re-use presentational components, but not container components. I disagree. You usually want to re-use some presentational components and not others, and you want to re-use some container components and not others.

This really just scratches the surface of what’s possible in React. Using some of these approaches can help manage the state of the world’s most complex user interfaces, and it’s how we do it at OpsRamp. Because, at the end of the day, even if we’re not as complex as a Facebook or Palantir, we want the end-user experience to be just as seamless, smooth, and satisfying.

Next Steps:

- Forbes: OpsRamp is one of the Best Cloud Companies to Work For in 2020.

- Read about our Winter 2020 Release in the blog.

- Subscribe to the OpsRamp Blog!